Watching a loved one move through the stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD) can be one life's toughest and most heart-breaking challenges. If we had to list examples of emotions by the distress they cause us, at the top of the list would be watching someone we love experience experience physical and mental pain that we cannot relieve. For many caregivers, next on the list at least for many caregivers, would be having to live with the fact that a loved one no longer recognizes us for who we are.

When my family members were residents of a care facility, I asked one of the nurses at the nursing home if my mother-in-law knew who I was. I was aware she could not have told anyone my name or my exact purpose in her life. That much was evident. However, I wondered if she knew that I was there to see her. The nurse assured me that seeing me step off the elevator was a highlight of my mother-in-law's day. I was glad of that. I felt my visiting her was important no matter what she "knew," but it was nice to hear those words from the nurse just the same.

Spouses and adult children of people with AD and other dementias often have to brace themselves for a time when their loved one no longer recognizes them.

Not Being Recognized Doesn't Mean We're Forgotten

The pain of walking into a room and having one's spouse or parent not recognize us can can be hurtful and trigger some strong emotions. Sometimes, adult children especially, will ask, "why should we visit them? Why go through the pain of sitting there, when they don't even know who we are?"

I can only give my own thoughts on this situation as an experienced family caregiver. What I say to people is that their loved one has not "forgotten them." Even though the person may not indicate in any way that your presence is known, it may well be that the touch of your hand, the sound of your voice or even some sense we cannot quantify will get through to this person, somehow.

A Person With Alzheimer's Can Still Feel

It is believed that people in comas often hear conversation around them. If this is so, how can we know for certain what a person locked in the fog of Alzheimer's really does, or does not, understand? I believe in touching people, caring lovingly for them, speaking to elders and treating them as functioning human beings, no matter what their condition appears to be. If you put forward your best effort to treat them in this fashion, they will have perceived whatever they are capable of comprehending. Hopefully, at the very least, they perceive that they are loved. After all, if they perceive more than is readily apparent, we would never want to be responsible for depriving them of interaction, love and comfort that they so desperately need.

Photo Timeline for People With Alzheimer's

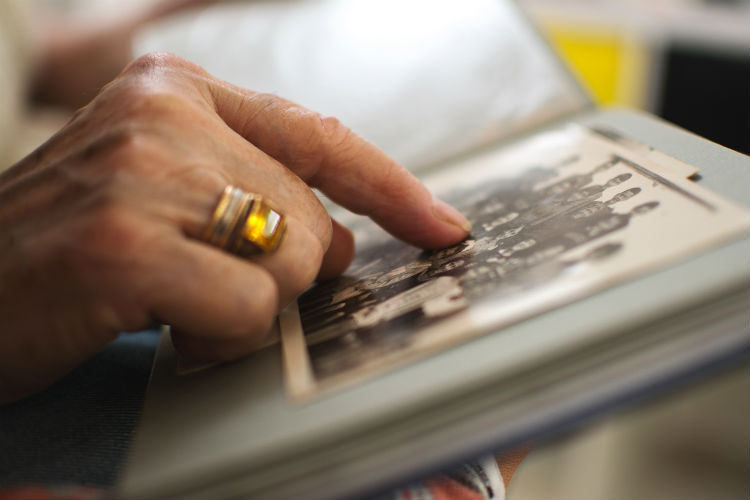

With AD, short-term memory is destroyed first. Therefore, while your spouse or parent may not know you as you look today (short-term memory), if you pulled out a photo album showing you 20 or 30 years ago, the person may recognize "you" immediately (long-term memory).

One commonly practiced technique is when people have searched through pictures from the past and made up a timeline of sorts. If, as an adult child, you choose to do this, your timeline will consist of pictures of yourself at various ages, from childhood on. Each picture will have a label underneath stating in large, black type with your name and age at the time of the photo. It is generally good to have your baby picture, a picture of you as a young child, one from your late childhood, your teenage years, your young adult years and so on, until there is a photo showing you as you look now.

This timeline can often trigger remembrance, as the person with Alzheimer's "sees" you age. They see you at say, 50, in person. The last photo on the timeline is one that shows you as you look now. As with all the others, your name is under it.

A spouse would probably benefit from starting the picture timeline during the courtship period. Either way, the exercise may trigger in a person with Alzheimer's some understanding of the role you have played in their life.

This exercise does not work for everyone, but the idea that it works for some people is intriguing. This technique may be short lived as the disease progresses, though. Even if this project does not have the desired effect of helping the person understand who you are, the exercise of looking at old photos is still stimulating and often fun for everyone.

Families Cope with Memory Loss in Different Ways

As with nearly everything in life, we all cope in our own way. Some people, while feeling deeply the sorrow of watching a loved one's decline, can still feel they are communicating on some level. The relationship changes, to be sure, but the person with the disease is still "in there," and we just keep working with the loved one in any way possible.

Others are so devastated that they have a hard time even being around someone they love who has changed so much. They do not want to visit a loved one with AD. This doesn't make them bad people, but my personal belief is that when we react in this way, we should do what we can to become educated about the disease or injury and learn how best to comfort and communicate with the person we love.

Don't Give Up on Your Loved One

Doing our best for those we love, no matter what their condition is, for better or for worse, will make most of us feel better in the long run. If we need a support group or personal counseling for caregivers to learn the skills we need to interact with a loved one affected by AD, the payoff from trying to do our best can be enormous. No day will be perfect, and often you will feel as though your efforts really do not count. That is normal.

However, trying does count. Do your best for those you love, even when it is hard. Do your best to learn and grow as a caregiver. You will not regret it.