A close friend of mine has been having a difficult time communicating with her mother, who is in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. This once lively woman can still enjoy a daily trip to the local coffee shop with her husband and hasn’t forgotten the names of her two children. However, my friend admits it’s hard to carry on a conversation with her mom these days. Sadly, she can’t remember if she’s repeating herself when she tells a story or asks a question, so she withdraws into her own world.

“I get very frustrated and sad, and then it turns to anger,” admits my friend (who didn’t want to be identified). “I remember how brilliant she was.”

Alzheimer’s patients often struggle to communicate with their loved ones, and my friend certainly isn’t alone in her feelings surrounding her mother’s decline. However, there is a pressing question that she and countless other caregivers have pondered: Why do dementia patients remember some things but forget others? How is it that this woman still knows her family members but can’t remember what she said 20 minutes ago?

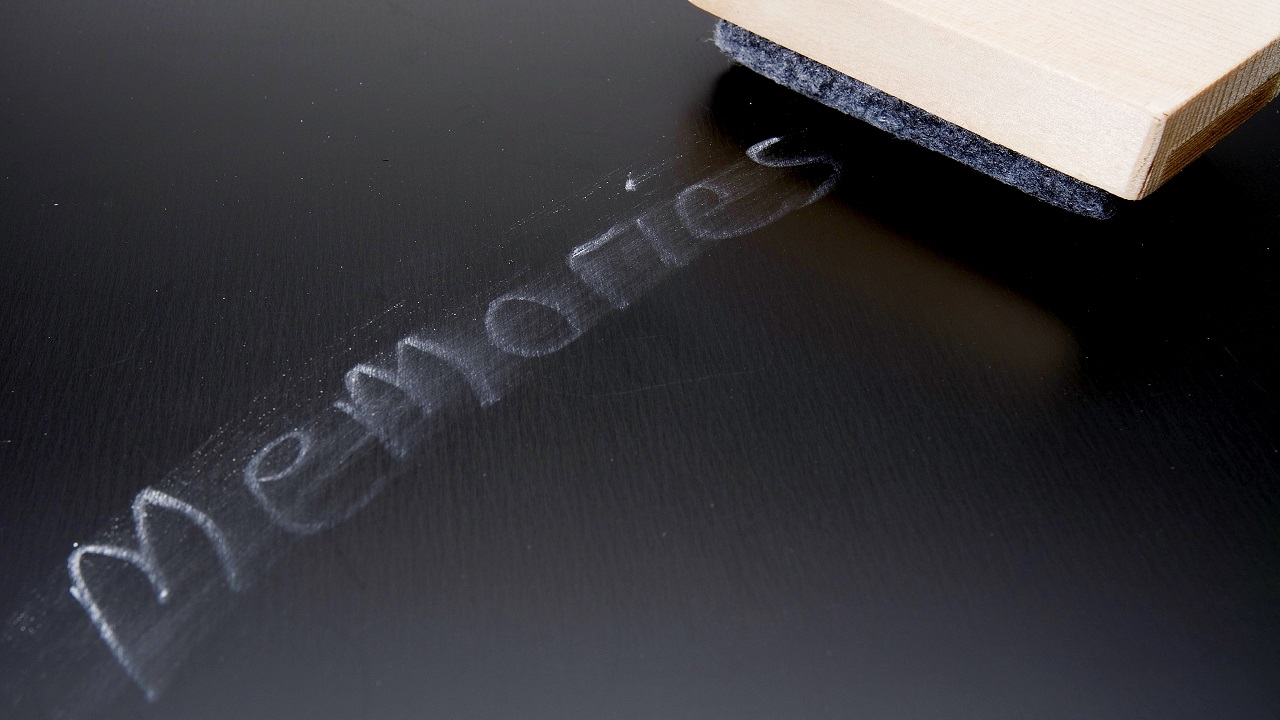

Learning how the brain forms, stores and recalls memories gives us a better understanding of why Alzheimer’s disease (AD) affects short-term memory and long-term memory differently.

How Memories Are Formed, Stored and Recalled

The brain is an extremely complex organ, and there is still a great deal that scientists and medical professionals do not fully understand when it comes to brain function, anatomy and disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. However, research in the field of neuroscience is booming.

On a very basic level, an area of the brain called the hippocampus is primarily responsible for memory and learning. When a person with a healthy brain learns something new or has an experience, it registers in the hippocampus, which encodes the information and sends it to other parts of the brain for storage. These “storage” areas, like the frontal lobe, also play an important role in memory recall.

A study published in the Journal of Neuroscience found that the age of a memory determines where it is stored (and recalled) in the brain. Healthy brains rely heavily on the hippocampus and associated structures for the recollection of more recent memories, whereas the frontal, parietal and lateral temporal lobes are responsible for the recollection of older memories.

First In, Last Out: Dementia’s Impact on Memory

There are many different types of dementia and each affects the brain in different ways. In Alzheimer’s disease, the hippocampus is one of the first areas of the brain to be damaged. One study found that hippocampal atrophy associated with early AD amounts to a 15 to 30 percent reduction in volume.

“The first thing that gets affected is the ability to take in new memories,” explains Amanda Smith, MD, director of clinical research at the USF Health Byrd Alzheimer’s Center and Research Institute.

When the hippocampus isn’t functioning correctly, it directly inhibits the ability to process and retain new and recent information. Since this information is never properly encoded, no memory is formed and therefore it cannot be recalled. This is why an Alzheimer’s patient might remember an event from 20 years ago but can’t remember what they did mere minutes ago.

“First in, last out” is often used to describe the peculiar pattern of memory loss that AD causes. This concept is a take on an inventory valuation method used in accounting. In this application, though, it means that one’s first memories like things learned in childhood and young adulthood (long-term memories) are the last to fade. The reverse is also true; more recent information is the first to be forgotten in Alzheimer’s patients.

Of course, as the disease progresses and affects larger areas of the brain, long-term memory and other cognitive functions are also impacted. Eventually, a person may forget their loved ones’ names, important relationships, where they live and other critical information.

Read: When a Loved One with Alzheimer’s Doesn’t Recognize You

Coping With a Loved One’s Memory Loss

Alzheimer’s patients experience a great deal of uncertainty, confusion, fear and frustration on a daily basis. So, too, do their family caregivers. Witnessing a loved one’s slow cognitive decline is very painful.

“It takes an emotional toll on the caregiver,” explains Louise Kenny, LCSW. “They grieve watching their loved one lose their memory.”

After more than a decade as a bereavement counselor at Avow Hospice in Naples, Fla., Kenny left her job to care for her aging father. She advises her fellow caregivers to educate themselves as much as possible about the diseases their loved ones have—especially dementia—so they will be prepared for whatever may lie ahead.

“Really understanding the type of dementia your loved one is going through will make caregiving a bit easier,” Kenny notes. “If you can, keep that in the forefront. Realize that it’s not intentional and that there are physical and neurological reasons for their memory loss.”

There are also some practical steps that family caregivers can take to better cope with the challenges and uncertainties that come with dementia care.

Follow a Regular Routine

Without a doubt, patience is an essential quality for dementia caregivers. Kenny recommends setting a daily routine for seniors with Alzheimer’s because they tend to thrive on familiarity and consistency. However, a certain degree of flexibility is needed to address fluctuations in a loved one’s mood and dementia symptoms.

Read: Why a Daily Routine is Helpful for People with Dementia

Practice Self-Care

Caregivers want to do what is best for their loved ones, but it’s also important to be mindful of your own physical and mental health. To avoid caregiver burnout, Kenny stresses the value of building a support network where you can share you concerns, fears and frustrations. Throughout her career, Kenny has seen how the world starts to narrow for caregivers just as it does for Alzheimer’s patients. Eventually, they find themselves terribly lonely and isolated.

Read: Improving Caregiver Well-Being

Remember to Laugh

Finally, Kenny advises caregivers to keep a sense of humor. At the moment, laughter is the best medicine for my friend. While her mom understands the seriousness of her diagnosis, she also likes to joke about her memory loss.

“My mom says she can laugh or cry, but she’d rather laugh,” my friend notes. “So, that’s what we do.”